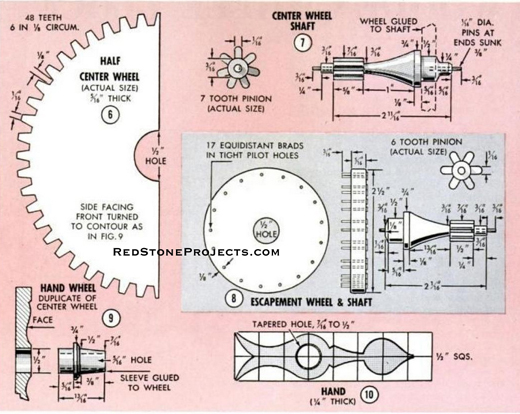

| Wheels and Shafts

In making the three-wheel shafts, Fig. 3, 7 and 8, first

drill the bearing-pin holes at the ends of the blocks in perfect alignment

before you do the turning. Slight misalignment can cause binding of pins

in bearing and wobbling of shafts and wheels. The drive-wheel shaft, Fig.

3, has a bearing pin at one end only. The other end rotates in a hole in

the front plate. You drill four pilot holes in this end for brads that

serve as a pinion to turn the hour hand. All the wheels and the ratchet

pulley have 1/2-in. center holes drilled before turning, and these are

used to mount the work on a threaded arbor. One side of each wheel that

can be seen in the assembled clock is turned to a pleasing contour. The

shafts are turned so the wheels fit them snugly. The hole in the ratchet

pulley, Fig. 5, is slightly oversize so it rotates on the shaft. The ratchet

pawl is pivoted on the side of the drive wheel and is kept in firm contact

with the ratchet by a music-wire spring secured by two tiny staples, Figs.

4 and 5.

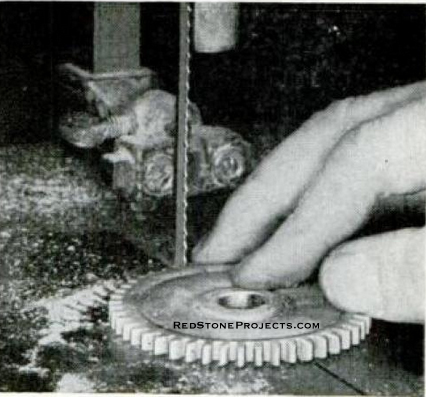

Cutting the Teeth

The gear teeth can be cut in different ways. One method

consists of laying off the teeth according to dimensions in Figs. 5 and

6, using a sharply pointed hard-lead pencil, or by tracing them from these

drawings. Remove the waste with a fine-tooth handsaw as shown in a photo,

scroll saw, or even a hand fret-saw, and dress down to the marked lines

with a small flat file or manicure sanding stick. Another method involves

the use of a router that slides on a track above the lathe, and an indexing

plate on the lathe spindle having the required number of indexing holes.

Get a restored copy of these Wooden Gear Clock Plans

with 11 Pages of Enhanced and Enlarged Figures and Illustrations

and Searchable Text.

All Orders Processed

On a Secure Server

|

Figure

3 through 5. (3) Drive-Wheel Shaft, (4) Half of Drive Wheel, and (5)

Ratchet and Cord Pulley

|

| Matching Wheels to Pinions

Check each shaft separately for easy rotation in the frame

so there is no trace of binding in the bearings. Match the drive wheel

to the 7-tooth pinion on the center-wheel shaft before gluing on the center

wheel. The fit between wheel and pinion will probably be tight so that

the wheel cannot turn freely or at all. Free the teeth by very delicate

dressing, but first blacken with ink the tip of one pinion tooth and the

tips of two-wheel teeth that straddle it when meshing. This assures subsequent

reassembling of pinion and wheel in exactly the same relationship.

To match wheel and pinion teeth, hold the frame in a padded

vise and gently apply a little pressure on the wheel in the same direction

that it will rotate in the clock, at the same time putting a slight drag

on the pinion to simulate actual working stresses. Carefully determine

just where binding occurs both when a pinion tooth starts to engage the

wheel teeth and when it disengages from them. A small piece of carbon paper

fed between the meshing teeth will show up points of excessive rubbing.

Dress only the slopes of the wheel teeth but not the tips

as this reduces the wheel diameter. Too much dressing ruins a wheel because

it produces excessive clearance and allows pinion teeth to strike the tips

of wheel teeth. Remove all high spots from the wheel teeth that tend to

slow rotation of the wheel when it is barely touched with your finger and

the pinion is kept under a slight drag. The tips of pinion teeth should

be semicircular in cross section and must not be dressed down on the top.

If the tips of the wheel teeth bind on the bottom of pinion gullets, deepen

them a trifle. After matching the drive wheel to the pinion on the center-wheel

shaft, glue the center wheel to its shaft and proceed to match it to the

pinion on the escapement-wheel shaft. This is done while the drive wheel

is removed. |

|

|

Figures 6 though 10. (6) Half Center Wheel.

(7) Center Wheel Shaft,(8) Escapement Wheel and Shaft, (9) Hand Wheel,

and (10) Hand

|

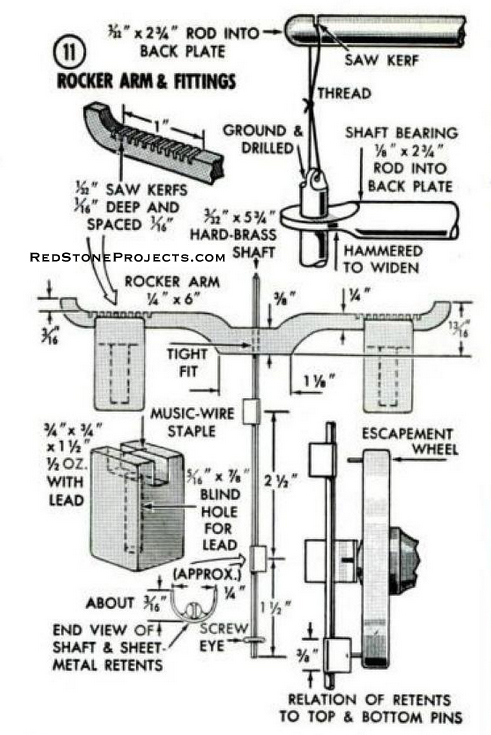

| Escapement Mechanism and Timing

Drill pilot holes for the equidistant brads of the escapement

wheel, Fig. 8. using glue on the brads for extra holding power. Uniform

height is obtained by grinding. Fig. 11 shows the rocker arm and associated

parts. Sheet-metal retents on the shaft alternately stop the escapement

wheel momentarily. Just before an obstructed pin is freed from one retent

the opposite one swings in to obstruct the pin moving toward it. Bend the

retents separately to proper shape on a nail of the same diameter as the

shaft, then slip them on the shaft and solder in place. Inside surfaces

of retents should be very smooth. After pressing the rocker arm on the

shaft, you can "snake" the latter into position down through the hole in

the upper crosspiece. When the shaft is set in its bearings and hangs from

the top pin by thread, the relents should swing about halfway over the

pins when engaging them. Adjust for this distance by moving the bearings.

Avoid contact of the shaft against the bearing pin of the escapement wheel. |

|

|

Waste between the teeth is first removed

with band, or scroll Saw, then filed to the line with a small flat file.

|

|

| The escapement mechanism will require delicate adjusting,

mostly by bending the retents in or out. If spread apart too far they won't

stop wheel rotation. If a retent lands and stops on the tip of a pin, the

spread must be decreased slightly. When the retents are too close the pins

cannot pass either of them.

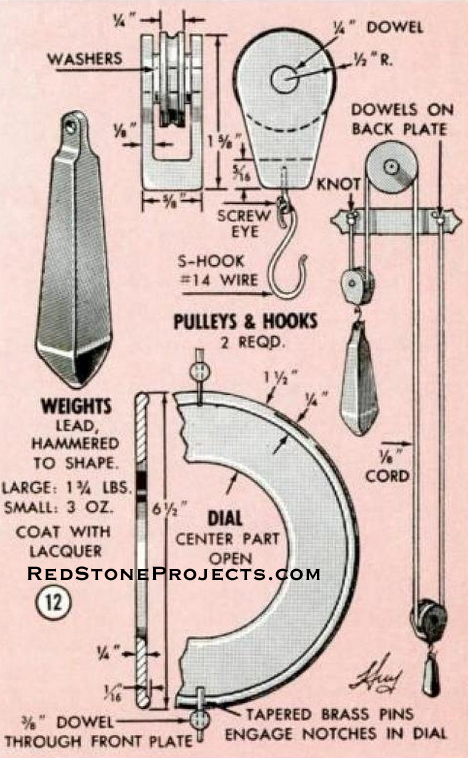

Two 1/2-oz. weights on the rocker arm can be shifted to

adjust timing. If this is not enough the rocker-arm weights are made lighter

for faster movement and heavier for slower movement. Fig. 12 details the

weight pulleys and cord. The latter goes through the anchor posts and is

knotted above each. If the cord slips on the ratchet pulley apply some

rosin. The pulleys must not bind in the sheaves, which may be enough to

stop clock movement. The 3 oz. weight serves only to keep the cord taut. |

|

|

Figure 11. Rocker Arm and Fittings.

|

|

|

|

Figure 12. Weights, Pulleys, and Hooks.

|

| Hour Wheel and Dial

The hour wheel is identical to the center wheel but is

glued to a sleeve, Fig. 9, which fits the dowel on the front plate. Fig.

10 shows the hand which is easy to loosen and tighten for changing its

position. A tapered brass pin slips through the dowel. The dial, also shown

in Fig. 12, surrounds the hour wheel and is held by tapered brass pins

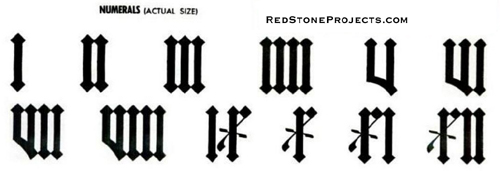

which also hold the front plate on the crosspieces. Numerals on the dial

can be done with India ink later covered with transparent lacquer. The

clock pictured here is a replica of one of the first hand-made, weight-operated

clocks. Making a copy of it will increase your admiration of bygone craftsmen.

The closeup view minus the dial, hour wheel and hand, shows the relationship

of the three time-keeping wheels and the escapement mechanism. These took

great skill to form before the advent of precision power tools. |

|

|

Wooden Clock Numerals

|

|